Judiciary & Courts Bill 'not worth the paper it's written on' as Scottish Parliament hears judges ask for 'a measure of trust'

The latest attempt at reforming Scotland's judiciary has been described as 'not worth the paper it's written on', by Lord McCluskey, formerly one of Scotland's senior judges, now a Labour peer in the House of Lords. The former Court of Session judge made the assertions during his testimony last week to the Scottish Parliament.

Lord McCluskey on judicial independence and proposed judicial reforms

As you know, I have criticised Lord McCluskey for his criticisms of proposed reforms to the legal profession and judicial system, but in this case, he is probably correct, and the Judiciary & Courts Bill itself, which is currently being heard by the Scottish Parliament's Justice Committee should be at the very least, cleaned up quite a bit, and quite a dose of accountability & transparency added to it.

For instance, perhaps a more open, transparent appointments system than simply leaving it to the Lord President to appoint judges, may bring a little more in terms of public confidence to Scotland's creaky self serving legal system, which doesn't seem to have any will to change with the times, and certainly not adhere to the public interest, rather, adhere to it's own ..

Lord Hamilton on judicial appointments - apply a measure of trust ...

The office of Lord President seems to enjoy far too many powers, lacking accountability to anyone as Lord Hamilton's comments seem to indicate, but that really sums up the whole of Scotland's legal system - lacking accountability to anyone but itself, which is why the rest of us are almost enslaved to it, even being denied access to justice when it suits the legal establishment to keep people out of the courts or even decide an individual be denied access to legal representation.

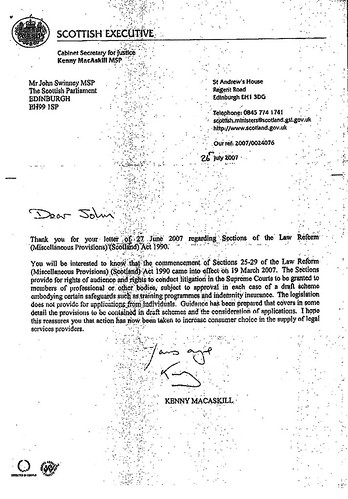

The Lord President, Lord Hamilton is involved in many appointments to the legal system, not just those of appointing members of the judiciary, and only recently his role, along with Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill in refusing all applications made by non members of the Law Society of Scotland to gain rights of audience & representation under Sections 25-29 of the Law Reform (Misc Provisions) (Scotland) Act 1990 brought into question the motives of the current legal establishment for keeping the legal services market closed, as a business monopoly for its own.

Such is the determination of the current legal big wigs to protect their own business markets and money making model, a leaked letter from the Justice Secretary to the Cabinet Secretary for Finance, John Swinney, sought to mislead Mr Swinney on the wellbeing and status of applications made under Sections 25-29, all of which have so far been struck down by both the Lord President and Mr MacAskill, ensuring that no one practices law in Scotland unless they tow the Law Society line and obey those currently in charge. Open legal markets we do not have yet then ...

Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill misleads Cabinet Colleague John Swinney on access to justice appointments ...

Revisiting Lord McCluskey's comments that the Judiciary & Courts Bill is not worth the paper it's printed on, this does bring back memories of former Scottish Legal Services Ombudsman Linda Costello Baker's comments against the Legal Profession & Legal Aid (Scotland) Act 2007, which she called "a mess", and of course as we now know, she was correct in her claims - the Scottish Legal Complaints Commission which has sprang from the LPLA Act, has been happily and easily co-opted by the Law Society of Scotland, and Ministerial appointments to the Commission itself have seen a bunch of lawyers and ex Law Society Committee members appointed to it, giving the air that it will be injustice as usual for anyone who has problems with a solicitor in Scotland.

You can read more about what former Legal Services Ombudsman Linda Costello Baker said on the half hearted attempt at reforming Scotland's legal profession via the LPLA Bill here : Last words from former Scottish Legal Services Ombudsman condemn the Scottish legal profession

My latest article on the demise of the LPLA Act and the Scottish Legal Complaints Commission before it has even begun its work can be viewed here : Funding argument over Scottish Legal Complaints Commission conceals lawyers interference in 'independent' complaints body

Do we call that reform ? I don't think so .... and no doubt the Judiciary & Courts Bill, if it does make it through the Justice Committee, may well go the same way as the LPLA Bill when it was at the Justice 2 Committee in 2006 ... voted through and passed into law .. then turned on its head to serve those it sought to reform, as any attempt at reforming Scotland's legal system seems to end up in the bucket.

Lord Hamilton on dealing with complaints against the judiciary ...

Maybe we should therefore listen to Lord McCluskey this time, and make sure that if the Judiciary & Courts Bill does go through, it serves a common purpose of transparency & accountability, not simply serving the judiciary itself..

I did notice one thing though ... a small detail I suppose, given the lack of standards within the Scottish Parliament itself ... anyway, Bill Aitken MSP is still the Convener of the Justice Committee and hearing this Judiciary & Courts Bill, but of course he was a JP himself, admittedly a JP isn't that high on the judicial ladder, however, as Annabel Goldie MSP as a solicitor herself and thus a member of the Law Society of Scotland, had to resign from the Justice 2 Committee in 2006 when it heard the LPLA Bill, I wonder what shifting standards policy the Scottish Tories are applying to themselves these days ? Obviously the conflict of interest one must be out of fashion now ...

You can read more about Annabel Goldie's resignation in 2006 here : Annabel Goldie does the right thing and resigns from Justice 2 Committee Convenership but it seems that having a JP in charge of hearings on judicial reform is, amazingly, not a conflict of interest ... those tories must be up to something then .. trying to make the bill fail perhaps ?

Here follows some coverage of the Parliamentary hearings from both the Herald and Scotsman.

Plan for Bill on judiciary ‘not worth paper it’s written on’

ROBBIE DINWOODIE, Chief Scottish Political Correspondent

The plan to enshrine in statute the independence of the judiciary, praised last week by Scotland's most senior judge, was described by a former solicitor-general yesterday as "not worth the paper it's written on".

Lord Hamilton, the Lord President told the Holyrood Justice Committee last week that the proposal in the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Bill "sends out the right message" against a day in the future when "conflicts could arise between the judiciary and the executive".

But yesterday retired judge and former law officer Lord McCluskey told the same committee: "The evidence you heard last week was, with respect, naive. The simple answer is it could never be more than symbolic, because if an unpleasant government came to power, then do you imagine it would not behave like the governments in Zimbabwe or Pakistan?

"If a party comes to power which does not respect democratic values then this is not worth the paper it is written on. Just as this Parliament could pass it a week on Monday, it could repeal it a week on Tuesday. This is actually worth nothing at all."

Lord McCluskey added: "Most countries in the world have a written constitution in which the independence of the judiciary is embedded in the constitution. Judicial independence lies in the hearts of men, not in constitutions and statutes of this kind, and I would rather it stayed there."

Calling the proposal "just a kind of gesture politics", he said: "The English needed it and so we slavishly copied the English. We have never had a statutory declaration in Scotland. We don't need to follow slavishly and plagiarise English legislation."

The bill would give the Lord President formal recognition as the head of the Scottish judiciary, making him responsible for matters such as the training, welfare and conduct of the judiciary. There would also be new procedures for appointing and disciplining judges and for dealing with public complaints.

The legislation also sets out proposals for modernising the machinery for sacking judges and sheriffs on the grounds of unfitness for office. They would be investigated by a tribunal chaired by a judge and containing a lay element.

Lord McCluskey said: "In my time there have been judges on the High Court bench who drank too much, who didn't do their homework, who didn't turn up. They were dealt with by the Lord President behind the scenes, and dealt with successfully, and that's the way it has to work."

On attracting a wider cross-section of society to the Bench, Lord McCluskey said: "I can see merit in the government, whether through the (judicial appointments) board or otherwise, taking steps to enable more people to acquire the skills that are needed to be a judge.

"But if I'm going to be operated on by a brain surgeon, I want the brain surgeon to be the best brain surgeon. I don't want him operating because he's black, Jewish, Catholic.

"It's the same with judges. It's the same kind of expertise which is required. I don't think affirmative action has any place in the selection of brain surgeons or High Court judges."

and now for the Scotsman's version, with a piece by Lord McCluskey himself first :

Why an 'English' bill won't fit Scottish justice system

By LORD McCLUSKEY

LORD McCLUSKEY shares his concerns about the judicial reform bill, which he believes is needlessly copying measures introduced south of the Border.

THE Scottish Parliament is about to devote much time and effort considering a Bill that is both unnecessary and misconceived. With the title, The Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Bill, it is unlikely to generate mass demonstrations around Holyrood.

Bewigged lawyers will not mount barricades proclaiming that "The End is Nigh". MSPs will probably approach the Bill in the belief that there must be some point to it: after all, it has been adopted by an SNP-led administration, having originally been proposed, in February 2006, in a consultation paper endorsed by Cathy Jamieson and Lord Advocate Boyd, as part of "our programme for reforming Scotland's justice system". The word "our" was and remains a serious misdescription: let me explain where the ideas in this Bill really came from.

On 12 June 2003, there occurred one of the most astonishing events in English constitutional history: yes, I do mean "English".

Downing Street issued a press notice announcing the abolition of the office of Lord Chancellor. When, within hours, it was realised that could not be done by Prime Ministerial diktat – because the office of Lord Chancellor had existed for eight centuries, the office holder was the head of the English judiciary with responsibilities under 374 Acts of Parliament, and only he could appoint judges in England and Wales – a second notice hastily appeared saying that it was "intended" to abolish the office. It was too late to save the then Lord Chancellor, Lord Irvine of Lairg: he retired to the backbenches in ominous silence. Lord Falconer of Thoroton took his place on the Woolsack and in Cabinet, with a brand new title, "Secretary of State for Constitutional Affairs".

What had happened? What did it mean for Scotland? What had happened was that David Blunkett, the home secretary, proposed to insert into the new Asylum and Immigration Bill an "ouster" clause, preventing the courts hearing legal challenges to the decisions of tribunals in asylum or immigration applications. The Lord Chancellor, rightly, regarded that as a totally unacceptable departure from the rule of law. Both remained adamant; someone had to lose. It was the Lord Chancellor who lost. But it would have looked bad to announce that the Lord Chancellor had been defenestrated for defending the rule of law, so it was declared that the job itself had been abolished. As Lord Hoffmann said: "His removal had to be dressed in the robes of high constitutional principle."

What did it all mean for Scotland? Not much. For in Scotland the Lord Chancellor had no significant functions. We had our own head of the Scottish judiciary, the Lord President. Judges here were appointed by the First Minister, advised by a Judicial Appointments Board. For Scots, the Lord Chancellor was as relevant as the Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard.

In England, by contrast, eight centuries of tradition and legal structures had to be demolished and replaced in a hurry. So the new secretary of state set about creating a fresh constitutional structure for the English legal system. He entered private negotiations with the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales. There was no place in these discussions for the Lord President, the First Minister, the Lord Advocate, the Advocate General, or Scottish Law Lords – not altogether surprisingly, because Scotland's legal system was not affected by the loss of the Lord Chancellor. The negotiations produced a "Concordat", providing new ways to carry out the Lord Chancellor's English functions. The new scheme was enacted in the Constitutional Reform Act, 2005.

The Lord Chief Justice was given a new title, "Head of the Judiciary of England and Wales". For appointing judges, England copied the Scottish system, creating a Judicial Appointments Commission. And, most interestingly, because the English regarded the Lord Chancellor as the guardian, within government, of the independence of the judiciary, it was decided that an entirely new guarantee of that independence was needed; so the new Act declared that government ministers had to respect the independence of the judiciary.

Of course, Scotland had no need of such an enactment, because the Lord Chancellor had no comparable role in relation to the independence of Scottish judges. Nor was any such role necessary, because Scottish public servants, both in government and judiciary, knew in their bones that ministers, like everyone else, had to respect, and invariably did respect, the independence of the judiciary. That fundamental tradition of respect had endured without challenge in Scotland for centuries without the need for a Lord Chancellor or a statutory declaration.

So what does the new Bill do? It slavishly copies the English Constitutional Reform Act, 2005. It creates a new title, "Head of the Scottish Judiciary" and confers it on the Lord President, along with numerous administrative functions that he has never had, or needed, and which will make unacceptable inroads on the time and energy he has for carrying out his real function, which is to safeguard and develop the unique character of Scots Law.

Next, it provides a "Guarantee of continued judicial independence". The word "continued" acknowledges that judicial independence already exists. And whose duty is it to provide that "guarantee"? Answer: the First Minister, other ministers including the Lord Advocate, and everyone responsible for the administration of justice.

Surely these public servants, especially the Lord Advocate, would be the first to declare that they already have such a duty at common law and that to neglect it by "seeking to influence particular judicial decisions" would be to pervert the course of justice.

As the "guarantee" imposes the duty only on those named, what about others, spouses, uncles and partners? What about Donald Trump? The simple point is that the duty created in the Bill already exists.

The Bill neither guarantees nor extends it. If anything, it limits it. It does not even create an offence of "influencing judicial decisions".

The Bill abounds in similar nonsenses, especially in relation to the appointment of judges. Let us hope that MSPs recognise its uniquely English features and have the courage to reject them.

Biggest wigs lining up to give evidence

By Jennifer Veitch

A PROCESSION of Scotland's biggest wigs lined up to give evidence at the Scottish Parliament's justice committee last week, convened by Bill Hamilton, including Lord Hamilton, the Lord President and Lord Justice-General, and Lord Osborne, one of our longest-serving judges.

Compared to a day in court, there was not much pomp or ceremony about the proceedings, with the judges looking almost ordinary in their suits and raincoats. But the fact that they were there at all, publicly discussing their role and the implications of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Bill, was extraordinary enough.

There has been much criticism of attempts by the former Scottish Executive and the current Scottish Government to bring forward legislation to reform the judiciary.

There are others who are better placed – including Lord McCluskey on these pages today, to analyse the detail of the proposals in depth.

But, having had the opportunity to listen to sat Tuesday's oral evidence, it became obvious to me that there is much about the way the current system operates that could be improved.

The headline-grabbing issue was of course Lord Osborne's criticism of the procedures used by the Judicial Appointments Board in hiring judges, namely the absence of any formal checks as to the performance or competence of candidates.

For example, he said no-one would bother to contact a sheriff principal to ask whether a sheriff was the subject of any disciplinary proceedings or outstanding complaints.

Lord Osborne also poured scorn on a system that relied too heavily on performance at interview, which he regarded as an unreliable indicator of suitability for the bench.

While interviews are of course a necessary evil for most people seeking less elevated positions, clearly the Judicial Appointments Board should be able to provide much greater reassurance that such jobs are being filled on merit, and only after a robust assessment of a candidate's suitability.

The problem is that it also emerged that judges apparently want to have it both ways. Lord Hamilton said that he still needs to be able to give a "tap on the shoulder" to fill temporary judge positions.

Given the huge workload and degree of responsibility that judges must bear, is this fair on either the candidates stepping up to the plate or the public whose fates may rest on their decisions?

The absence of a formal complaints procedure for those who wish to raise concerns about the conduct of a judge – as opposed to using the appeals process to challenge a judicial decision – was also a concern.

Lord Hamilton was not able to give a figure as to the number of complaints that he receives about judges' conduct. No doubt when he produces the figures, as requested by the justice committee, it will emerge that he does not receive that many at all.

But, however small the number, there should be a far greater degree of openness and transparency about the rules and procedures involved. To leave everything to the discretion of the head of the judiciary, no matter how upstanding a fellow, seems too heavily weighted against the complainer.

The argument that introducing a formal complaints procedure would lead to more complaints simply does not hold water.

Surely there could be discretion to weed out vexatious or frivolous complaints? And, more importantly, there could also be an opportunity for the judiciary to learn from the few complaints that might actually be justified.

The Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Bill may well be flawed, and the justice committee may well want to suggest amendments before the bill proceeds to the next stage in the parliament.

But the judges have already demonstrated that the issue at stake here is not whether change is necessary or desirable, but whether the Bill as drafted offers the best way of going about it.

No comments:

Post a Comment